UC graduate student strike ends

Written by Chenya Kwon

The best laid plans of UCs and UC strikers often go awry.

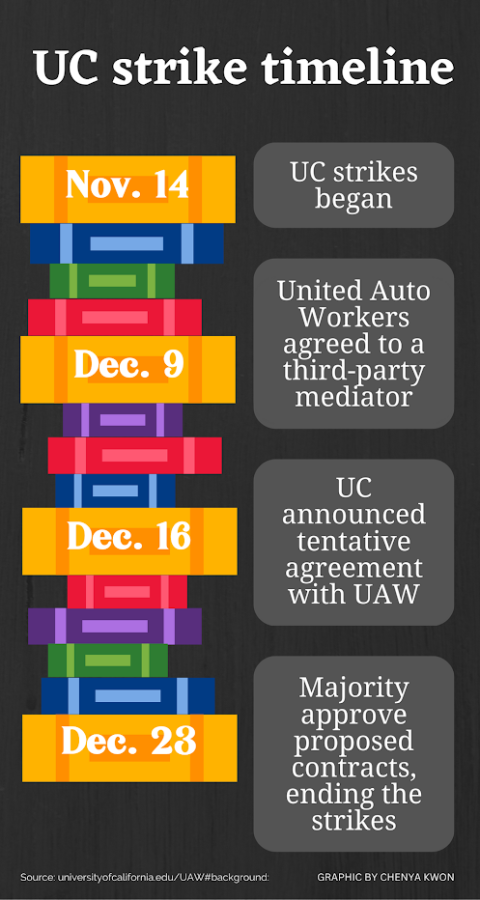

That was the case for the UC graduate student strikes that occurred throughout the final months of 2022. Though the unions were able to achieve the improved working conditions they sought, their unionization came with a few unintended consequences.

Unions first began in the 18th century during the Industrial Revolution, according to Ronni Sandford in Investopedia. These labor unions bargained with employers to create contracts that would change current working conditions.

“When you look at the history of the United States, all modern-day labor laws have been won through the collective solidarity of the working class,” said CP Government teacher Jacob Grise. “So, when we look at why is it that we have an eight-hour work day instead of a 10-hour work day, it’s because unions fought for them.”

Similar to the fight for shorter work days, UC graduate students also joined together to demand higher wages and other benefits. UC unions were primarily motivated by skyrocketing housing costs. In fact, 92% of UC graduate student workers spend a third of their income on rent as of Dec. 23, 2022, according to Tracy Rosenthal in The New Republic.

“I think that the working conditions during the pandemic made people realize it would be good to have other people on their side and band together to make changes necessary instead of just every man for himself,” said Julie Speerstra, WHS representative in the Unified Association of Conejo Teachers.

On Dec. 23, the UC strikes came to a close after the majority of union members voted for the proposed contracts that would “increase wages for all workers, including pay increases of up to 80% for some with the lowest compensations,” according to Catherine Hamilton in the Daily Bruin.

Over 20 days later, the contracts have had a noticeable effect on UC graduate student workers.

“My chemistry TA from last quarter who was also part of the strike was really big on talking about how he was underpaid and overworked,” said UCLA undergraduate Rachel Lee. “I saw him today and he seemed a lot happier now that they have come to a compromise.”

In stark contrast, UC students appear to be struggling with negative aftereffects.

“I have a few friends now who still don’t have any of their grades from last quarter put in which is very crazy because we need those for our grade book,” said Lee.

In essence, the strikes have benefited some, primarily graduate student workers, and harmed others, primarily undergraduate students. The oxymoronic result leaves some troubled.

“There are two sides to every problem,” said Becky Mertel, college and career guidance specialist. “There should be a way of dealing with problems so there’s not an innocent hurt during the resolution.”

Even outside of the UC system, the strikes have caused ripple effects, particularly for labor unions. Alongside factors like inflation and student debt, the strikes are believed to have also encouraged a spike in unionization throughout academic environments.

“In 2022 alone, graduate students representing 30,000 peers at nearly a dozen institutions filed documents with the National Labor Relations Board for a union election,” wrote Teresa Watanabe in the Los Angeles Times. “[The institutions] include USC, Northwestern, Yale, Johns Hopkins, the University of Chicago, Boston University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ”

This trend in universities is in direct parallel with pandemic-induced inflation and the public’s union support being at a “57-year high”, according to Jaclyn Diaz in NPR.org.

“People are starting to discover that they can’t survive off the low wages they have with the cost of living rising at a substantial rate,” said Grise. “All they’re trying to do is survive.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Westlake High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Anonymous Goat • Apr 1, 2023 at 4:41 pm

WOW! WHAT A fantastic! post :0 I was truly inspired by the content in this post. Keep up the great work!